For the last weeks I tried to figure out why “Ben” (Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve) would go for “QE2” (Quantitative Easing – part II) when “QE1” was not very effective in terms of stimulating the economy. It did not make much sense.

My conclusion is that the Fed has run out of options, but doing nothing is not an option, especially when there are more and more politicians vowing to reign into the Fed, and may be even change their mandate (currently being “full employment” and “price stability”).

May be Ben felt like the interviewee in the Monty Python classic “Job interview” sketch, where Cleese demands “Well, do something!” (2:50min):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dWMIuipn_c

So if the Fed is doing “something” just to do something, it won’t be effective. On top of that there are (lonely) voices claiming that exchanging Treasury bonds for reserves is not inflationary at all (witness the recent 0.6% core inflation number). So Ben might actually be right when he says that quantitative easing is not meant to be inflationary nor meant to depreciate the dollar. The problem of course being nobody believes him, and gold, silver etc going ballistic. And that’s exactly what he intended. It’s Ben’s Big Bluff.

Let’s look at what has happened so far. Excluding the latest announcement of additional $600bn purchases of Treasury bonds the Fed announced “quantitative easing measures of up to $1.75trn (200bn GSE debt, 1.25trn MBS, 300bn Treasury bonds – for a detailed overview see http://money.cnn.com/news/storysupplement/economy/bailouttracker/). This amounts to 12% of GDP (14.57trn as of June 2010). The Monetary base duly increased from $843bn (August 2008) to 1,963bn (October 2010).

However, broader measurements of money, like M2 or MZM (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_supply#Empirical_measures for explanation) do not show a similarly strong increase; in the time frame mentioned above, M2 rose from $7,787bn to $ 8,766bn (+13%) and MZM from $8,753bn to $9,695bn (+11%).

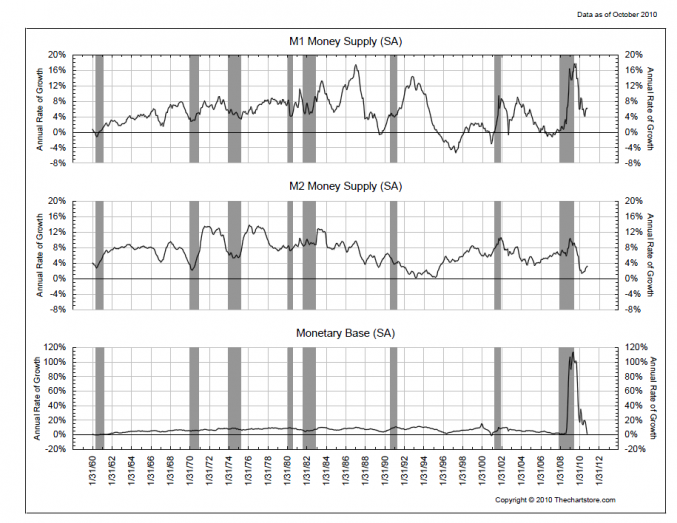

Note the declining growth rates for all major measurements of money supply (back to zero for the monetary base):

Annualized growth rates for M1, M2 and Monetary Base as of 10/2010. Source: TheChartStore.com

Annualized growth rates for M1, M2 and Monetary Base as of 10/2010. Source: TheChartStore.com

Why has the Fed not been more “successful” in increasing money supply? Two explanations come to mind:

(1) Decline in securitization. Until the financial crisis a lot of debt (mortgages, loans etc) had been securitized and sold off to other investors, freeing the originator up to engage in new debt. This has come to a near-standstill and led to a decline in the velocity of money.

(2) Deleveraging of private households, banks, shadow-banks and corporates. If I chose to pay down my credit card debt, my available cash balance goes down as well as the corresponding claim at the credit card company.

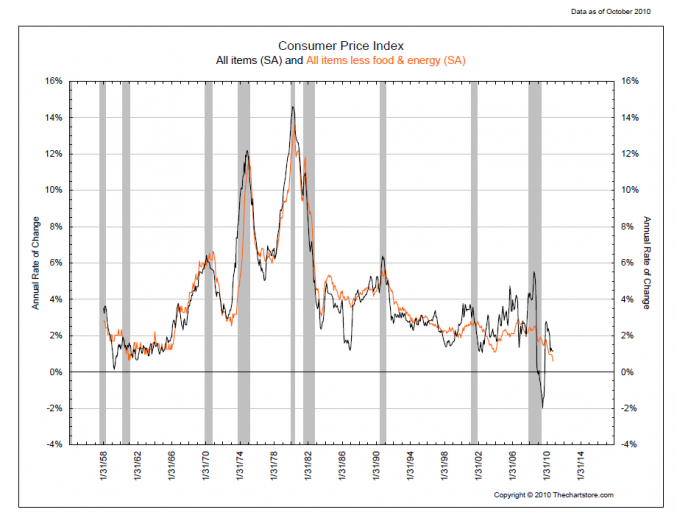

It should come as no surprise that core inflation (excluding food and energy), despite all hysteria to the contrary, has slowed down to levels not seen for many decades:

U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) including and excluding food & energy – October 2010. Source: TheChartStore.com

U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) including and excluding food & energy – October 2010. Source: TheChartStore.com

The year-over-year change in core CPI reached a level of 0.59% in October 2010 and looks to be trending even lower. Deflation is not out of the question. Deflation, of course, would be bad for entities with high levels of debt (first and foremost the banks). The Fed will try to fight deflation (as we pointed out in this post: https://www.lighthouseinvestmentmanagement.com/2010/10/26/why-the-fed-is-fighting-deflation-tooth-and-nail/). It seems the Fed is losing the fight.

Why would the Fed’s asset buying (and therefore injecting money into the economy) not be inflationary?

Let’s look at a POMO (Permanent Open Market Operation; for details see here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_market_operations): The Fed buys Treasury (or other) bonds from 16 Primary Dealers (PD’s, list: see here http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primary_dealer). The bonds move from the PD to the Fed, and the Fed credits the PD’s account at the Fed with the corresponding money. So far so good. Banks have to maintain a certain level of minimum reserves at the Fed in order to be able to give loans to their customers. In theory, higher reserves would allow banks to hand out more loans to their customers. This does not happen currently since

(1) Banks already have high levels of excess reserves at the Fed, and adding more does not help anything

(2) Banks have become much more careful in approving loans to customers (after getting burned with lax underwriting standards)

(3) Customers try to deleverage and do not apply for more loans (or do not qualify due to bad credit scores).

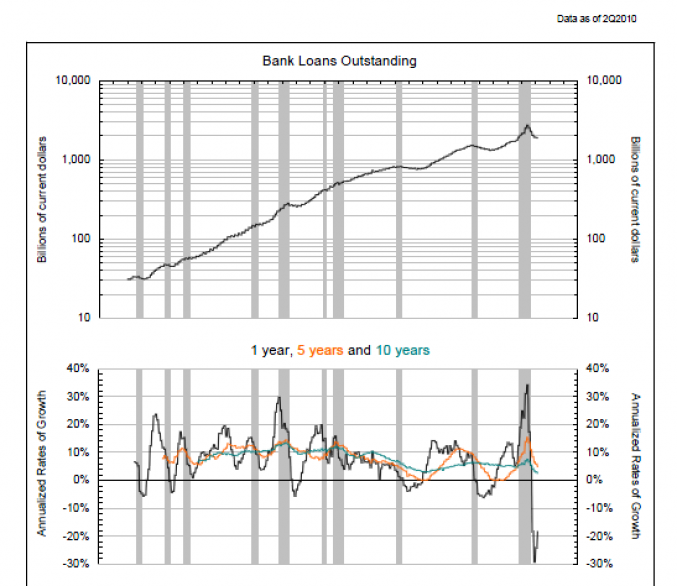

Look at the growth rate of total US bank loans outstanding (-20%!):

Total US bank loans outstanding as of 2010-Q2. Source: TheChartStore.com

Total US bank loans outstanding as of 2010-Q2. Source: TheChartStore.com

Conclusion: All “Quantitative Easing” does for the banks is exchanging low-yielding Treasury bonds (i.e. 5-year at 1.5%) into reserves at the Fed yielding even less (0.25%).

So far so good. But what if the Primary Dealer purchased that Treasury bond from a “non-bank” just before handing it to the Fed? Wouldn’t that put more money into hands willing to spend? Could be, but the strong inflows into bond mutual funds together with an increase in the savings rate point to private individuals rather cutting back on spending.

Up to here, nothing inflationary about “Quantitative Easing”.

Alright, but what is “printing money” then? Simply put, money is created when the government issues more debt (via the Treasury) than is covered by tax receipts. Current budget deficits are financed by issuance (net of redemptions) of new Treasury bonds. So at the end of the day, isn’t the Fed just monetizing a corresponding increase in government debt?

Yes, unless the increase in debt by the government was not over-compensated by an even larger decrease in borrowing by the non-government sector (as discussed in A. Gary Shilling’s “Insight”, November 2010, page 3).

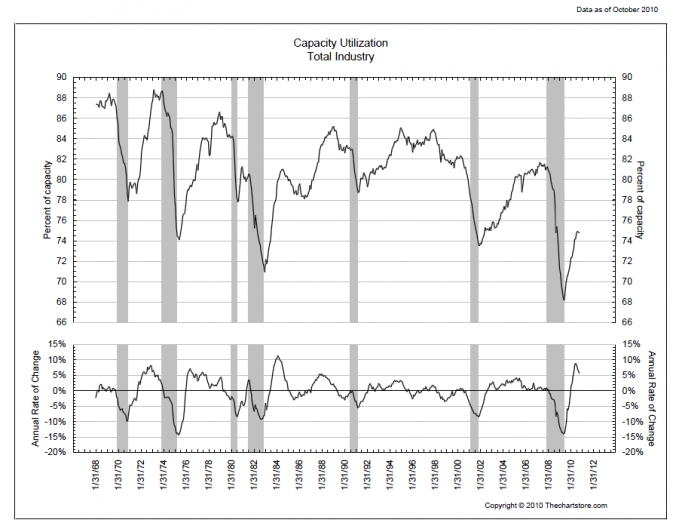

Finally, capacity utilization in the US is still at levels (74.8%) usually seen during the darkest days of previous recessions:

US Capacity Utilization – October 2010. Source: TheChartStore.com

US Capacity Utilization – October 2010. Source: TheChartStore.com

Example: Producer “A” has only orders to keep 3 out of 4 machines (75%) busy. Same for producer “B”. If “A” hiked his prices by, say, 5%, “B” would be more than happy to increase his production to 100% capacity by turning on this 4th machine, benefiting from customers switching from “A”. A’s capacity use would drop to 50% (2 machines), at which point he better reverse his price hike.

As long as there is “slack” in the system, price increases are very hard to push through. Pricing discipline is usually not good. And customers know that.

You could argue that Zimbabwe (the world record holder in inflation; more here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zimbabwean_dollar#Hyperinflation) probably has never had a problem with high capacity use (I unsuccessfully tried to find data). The problem here was clearly the actual “printing” of money (money only has a value when it is scarce). In the US however, increases in broad money supply have been modest, and growth rates have already trended sharply lower.

So if the Fed’s “Quantitative Easing” really is nothing but a big bluff – what are the consequences? Eventually, market participants will call it a bluff (when, for example, core inflation turns negative). This would have profound consequences for all asset classes thought to be benefiting from inflation (gold, silver, stocks, real estate).

What would the Fed do then? Buy more asset (classes)? Municipal bonds (as local governments struggle to balance budgets)? Corporate bonds? Houses?

It will become increasingly difficult for the Fed to continue on its current path as Congress will reign into this alleged “money printing”.

CONCLUSION:

“Quantitative Easing” is not inflationary as long as reserve creation does not translate into credit growth. Apart from a temporary increase in the price of assets purchased (or decline in yield) any positive effects on the economy depend on market participants “believing” in an inflationary effect (which will not materialize). The bluff will be called by future data (consumer price index).

Alexander F. Gloy is founder and CIO of Lighthouse Investment Management