In his book “More money than God”, Sebastian Mallaby describes how George Soros received a signal from Helmut Schlesinger (president of Bundesbank at that time), to go ahead and speculate on a devaluation of the Italian Lira and the British Pound.

Germany had enjoyed a boost from the integration of Eastern Germany, which, partially due to a generous 1:1 exchange offer for the Eastern German Mark, led to unacceptably high inflation. Despite numerous warnings from the Bundesbank, fiscal policies did nothing to reign into the growing threat to price stability. Seeing its advice ignored, the Bundesbank fought back and raised its discount rate all the way to 8.75%.

This caused problems for other European countries, who were forced to follow the Bundesbank unless they wanted to risk a weakening of their currencies. They had to apply a restrictive monetary policy despite their own economies just recovering from the recession of the early 90’s.

According to Mallaby, British finance minister Lamont had insulted Schlesinger at a meeting, trying to extract a promise to cut German interest rates. Despite Schlesinger’s refusal, Lamont led the press to believe Schlesinger had made concessions.

The “payback” didn’t wait for long; Schlesinger publicly denied any intention of cutting rates. He also expressed low confidence in the fixed relationships among European currencies, particularly the “unsoundness” of the Italian Lira.

This was the go-ahead for George Soros to attack the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. Mallaby:

“Schlesinger’s answer was as clear as Soros could have wished for. The Bundesbank was open to the idea of monetary union, but not at any price. It’s first priority was to preserve the proud tradition of the inflation-proof Deutsche Mark, and if other economies could not stomach the austerity this implied, well, then they should devalue.”

“Soros suspected that Schlesinger would be perfectly content to see his hard line on inflation sabotage the plans for European monetary union, since that union would involve the creation of a European central bank, which would supplant the Bundesbank.”

“All bureaucracies are motivated by self-preservation, Soros reflected, and Schlesinger, a career Bundesbank official, was surely the personification of this tendency.”

Ironically, 20 years later, a similar setup emerges, albeit with (so far) fixed exchange rates. While Germany enjoys the lowest unemployment rate of the last two decades, its European trading partners are re-entering into recession.

In the run-up to the umpteenth Euro-summit last week, most market participants expected the ECB to “reward” politicians with the long-awaited “all-in” action of purchasing increasing amounts of PIIGS government debt.

If you haven’t done so, I recommend listening to the ECB press conference Q&A session (16 minutes into the webcast). Draghi expresses surprise about market expectations the ECB would step up bond purchases after the summit. Draghi subsequently repels any attempt at extracting any concessions whatsoever.

Minute 36: “Why is it so impossible for the ECB to act like the other central banks? –” We have a treaty: price stability and no monetary financing”

Minute 59: “Why wouldn’t it be okay for Euro-zone central banks to lend to the IMF?” – “I think each central bank has its institutional set-up. The primary mandate of the ECB is price stability. In the US the primary mandate of the Fed is completely different from us. Same is for the Bank of England”.

Draghi left no room for ambiguity or interpretation. Every single attempt to extract some hope of monetary creation was cut up, diced and discarded. It couldn’t have been clearer. Draghi mentioned the “principles of the Bundesbank”. The spirit clearly lives on. Those that claim the Bundesbank intentionally encouraged speculators to attack the British Pound in order to expel it from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992 might find another example of “creative destruction” in front of their disbelieving eyes.

How this could be good for equities (Friday’s rally) is a mystery to me. But then again, the S&P 500 celebrated a new all-time high in October 2007, mere four weeks before the official start of the “great recession”.

The answer to the question “why would the Bundesbank intentionally crash the Euro” lies in the TARGET2 system of intra-Euro central bank payments. Izabella Kaminska of FT Alphaville describes how the Bundesbank has run out of assets to sell in order to fund other Euro-zone central banks. This in itself is quite amazing. The Bundesbank and the Dutch Central Bank seem to be financing the entire Euro-zone central bank system. As the music stops, the Bundesbank is taking away all chairs at the same time.

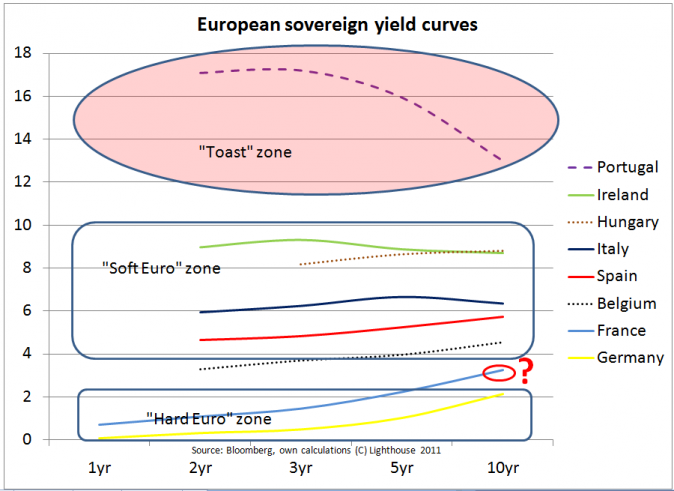

Merkozy are still trying to save the Euro by severe austerity at the last minute, but it is too late. Financial markets have already revolted and put countries in various buckets via yield curve “triage”:

The ghost of the Bundesbank has reappeared, this time under the disguise of an Italian. Ignore its powers at your own peril.