As I was traveling through Vietnam in the mid-nineties our bus drove through an area visited by a taifun. The road was running on a slightly elevated dam, so initially there was no obstacle to continue the journey. Looking out of the window there was water on both sides as far as the eye could see. Eventually the water rose to overflow the road, but the bus kept going.

A Volkswagen transporter, after having passed the bus in a moment of exuberance, was soon found in the ditch with water up to the roof – there was no way to tell where the road ended and the ditch began. The water rose further and started entering the bus through the front door. Still, the driver kept going. I was amazed at how little damage occurred despite the vast flooding. The flood waters slowly receded towards the ocean. Uninhibited by any dams, the water had enough space to expand.

At one point, the water had washed out the elevated road, and a gaping hole forced even our bus to stop. I thought this to be the end of the trip. Miraculously, a bunch of locals showed up, and, with the help of a bulldozer, quickly filled the hole with large rocks. All passengers were asked to de-board as the bus slowly wiggled across the rocks. And we were ready to resume our trip. Closer to the coast we saw the effects of wind damage; at least every third home had been cut in half by a fallen palm tree. Pigs and chicken ran around disoriented, as their barn had probably disintegrated. Despite the damage there was no feeling of this being a catastrophic event; the houses would probably be repaired (they were covered with palm leaves) within a few days, and life would get back to normal.

Compare this to what happens in our “developed” countries when house prices decline by 10 or 20 per cent: the wheels of the entire financial system come off.

I am not suggesting we all live in thatch covered huts. But building higher and higher dams with flimsy sandbags just increases the pressure (and leads to much greater damage when the dam finally breaks).

Look at how Euro-zone politicians and central bankers are increasing the risks by building higher and higher dams with flimsy sand bags. Nobody seems to understand why the water (debt) rises – and nobody seems to understand how to shut of the water. All they can do is building dams.

Euro crisis: amateur hour at the EU

For Angela Merkel time is running out. Until now she was able to use the threat of the German constitutional court to extort concessions from other countries. The Bundesverfassungsgericht is expected to rule on a bunch of cases challenging the legality of the Greek bail-out, the EFSF (European Financial Stability Fund) machinery, and ECB (European Central Bank) bond purchases possibly in February. On its website only two (unrelated) decisions are scheduled[1].

According to Der Spiegel, German Chancellor Merkel will launch a new “pact for competitiveness” to save the Euro-zone at this week’s EU summit.[2]The key points:

- Harmonization of tax rates (hello Ireland – yes, you guessed it, the corporate tax heaven is about to end, and companies will leave Dublin, making the recession even worse)

- Adjustment of retirement ages (hello France – you set cars on fire when the government dared to increase it to 62 years – wait until you are “upgraded” to the German level of 67 years)

- Improve job opportunities; mutual recognition of professional qualifications (please – what does this have to do with the debt crisis)

- A “debt brake” to stabilize public finances (weren’t the Maastricht criteria supposed to limit public deficits and spending? Oh, wait, Germany and France decided to abolish them when they themselves were unable to fulfill them).

Give me a break. Are you serious, Mrs. Merkel? This isn’t even worth discussing.

Let’s take a look at a proposal apparently being discussed in financial circles. Somebody had a brilliant idea: given Greek government bonds trade at around 70% of par why not have Greece buy back those bonds at a discount – with more loans from the EFSF?

Suddenly economists figured out that IMF predictions of Greek debt-to-GDP peaking out at 150% in 2013 were pure fantasy as now 160% seems more likely.[3]

And what do we need to hear from the Irish Central Bank? Irish GDP “will probably rise by 1% this year instead of 2.4% forecast in October, after falling an estimated 0.3% in 2010”[4] Remember the “National Recovery Plan 2011-2014”? It was based on real GDP growth of 0.25% in 2010, 1.75% in 2011 and 3.25% in 2012[5] (Irish Central Bank now says GDP “may expand by 2.3% in 2012). When will politicians and central bankers stop embarrassing themselves?

Back to Greece: Apparently the plan is to lend Greece another EUR 50bn and, get this, extend the maturity of existing loans from 3 to 30 years. [6] Greece would be able to buy back part of its own debt with the fresh loans and reduce the debt level (since debt is bought back below par, at, say 75%). This would be a “voluntary” debt restructuring (nobody is forced to sell at 75%) and hence not trigger a default (with unpleasant consequences for banks).

Let’s assume the plan works. 75% of EUR 50bn equals 37.5bn, saving 12.5bn. Greek GDP was EUR 330bn in 2010, so that’s less than 4% of GDP. Debt-to-GDP will still go up to 156% (instead of 160%). Still unsustainable.

Further: the ECB has been buying EUR 76.5bn of European peripheral bonds, predominantly Greek, Irish and Portuguese bonds. Will the ECB sell its bonds back to Greece at a loss (that would be a hidden subsidy by the European taxpayer)? What about the Greek government bonds pledged as collateral at the ECB? The owners (Greek banks) surely do not want to (and are unable) take a loss on these bonds. Why would a private investor sell at a loss when Mrs. Merkel “guaranteed” no losses from sovereign bonds until mid-2013? Moral hazard all over again.

If a country cannot pay back its debt you give more loans to the right hand so the left hand can give some money back? Please. Who comes up with this half-baked stuff?

An accounting identity: fiscal, private sector and external sector balances

Back to economics school: GDP (the” production” side) can be calculated as

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

where C= consumption spending, I = investment (private), G = government spending and (X-M) the difference between exports and imports.

On the “spending” side, people can use their income to consume (C), pay taxes (T) or save (S).

GDP = C + S + T = C + I + G + (X -M)

or:

S + T = I + G + (X-M)

or:

(S-I) + (T-G) – (X-M) = 0

or:

(S-I) + (T-G) + (M-X) = 0 [8]

where:

(S-I) = domestic private sector financial balance (positive value is a net saving or surplus position)

(T-G) = government financial balance (a positive value is a fiscal surplus)

(M-X) = foreign financial balance (the inverse of the trade deficit [X-M]; a trade deficit is foreign net saving)[7]

Nice letter soup, you might say. But what does it mean?

In economist gibberish, the domestic private sector financial balance (S-I), the fiscal balance (T-G) and the foreign financial balance ([M-X], the inverse of the net external balance) must add up to zero.

In plain English: Savings of households and companies plus budget surplus/deficit plus trade balance must add up to zero.

Meaning: If a country has a trade deficit (X – M < 0), it must have either a budget surplus (less government spending than tax revenue – rarely seen) or the private sector (households and companies) has to dip into savings (or rack up more debt). In the long run this leads to either an indebted domestic private sector or, if foreign savers buy domestic bonds, more and more debt service towards foreign entities (or both). This is what happened in Europe and is the source of the problem. Whoever does not understand these national accounting rules does not understand the problem, and hence cannot solve it. It’s so simple – yet so widely ignored.

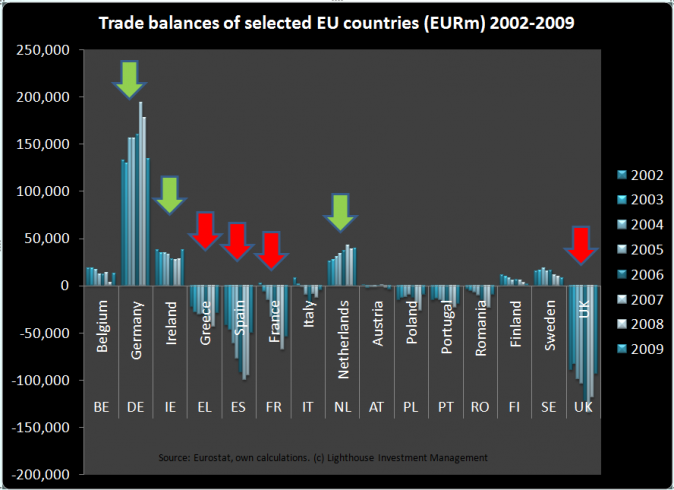

Let’s look at the trade balances of select EU members over the past few years[9]:

While Germany racks up a nice positive trade balance (more exports than imports), other countries (UK, Spain, France and Greece) have notorious trade deficits. Apart from Germany, only the Netherlands and Ireland (!) have significant positive trade balances – in absolute terms[10].

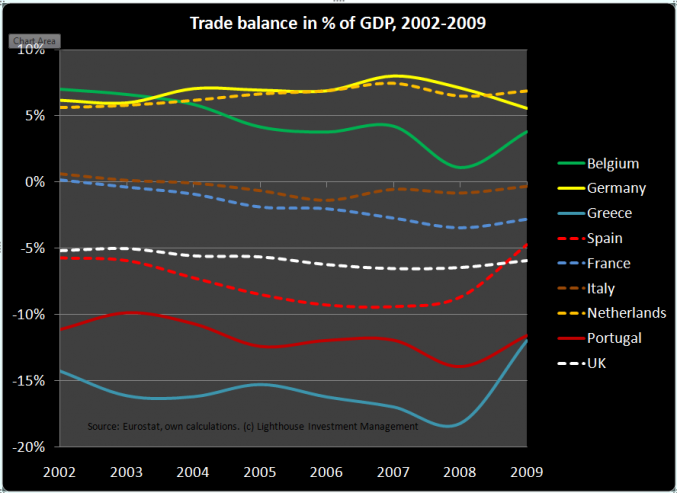

Now let’s look at the same data, but relative to the size of the economy[11]:

On a relative basis you can see that Greece, Portugal, UK and Spain have trade deficits in the range of 5-20% of GDP. Remember (S-I) + (T-G) + (M-X) = 0 ?

In country with a trade deficit in the order of 10% of GDP, either the government (T-G) must run a budget deficit of 10% of GDP or the private sector (S-I) must dip into savings (or rack up debt) to that magnitude. Or a combination of those two.

A large trade deficit leads to imbalances for the fiscal and/or private sectors

Think about it this way: a trade deficit means more goods are coming into the country than leaving the country. Those goods need to be paid. Meaning more money is leaving the country than coming into the country. A trade deficit needs to be financed. In the long run, this leads to increased debt levels. It is unsustainable.

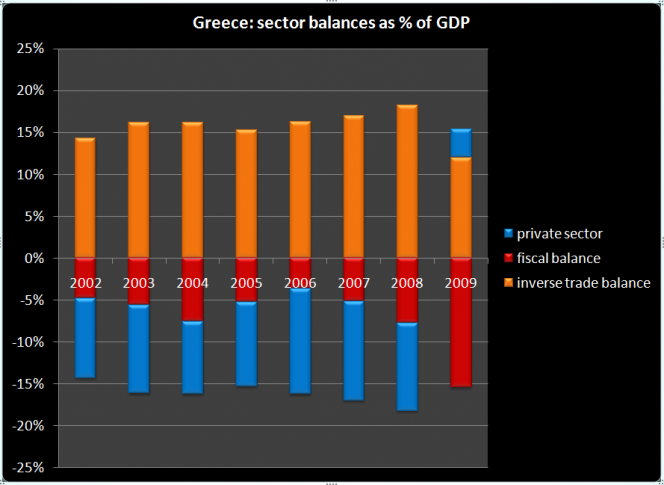

In the case of Greece we have trade deficits in the area of 15% and a 2009 budget deficit of 15.4%[12]. The fiscal sector balances have developed as follows: [13]).

Now that Greece has reached a (public) debt-to-GDP ratio of 115% (as of 2009) and its banks are insolvent (hanging on thanks to loans from the ECB) the Germans roll in and demand a reduction in deficits. The fiscal deficit is driven by the trade deficit and the impossibility of further leveraging by the private domestic sector. The only way out would be to reduce the trade deficit.

How do you improve your trade balance? Increase exports. How do you achieve that? Make products more competitive or desirable. How? Make them cheaper. How? Devalue your currency. Oops. We’re in the Euro-zone. Can’t do that.

The trade balance will not be of much help in reducing the deficit (except for reduction in consumption of imported goods by Greek consumers due to financial hardship).

What is left is a further increase of debt by the private sector (households, banks, companies) – the last thing Greece needs. It will lead to further financial instability.

Of course, one way out of the problem could be “internal devaluation”: since you cannot change your exchange rate, domestic wages and prices would have to fall to regain competitiveness and improve the trade balance. This would mean severe deflation. Apart from social unrest this usually means bankruptcies and banking crisis.

Despite forcing Greece into a combination of deflation, high unemployment and financial instability the Germans say “Just be like us”. Is that at all possible?

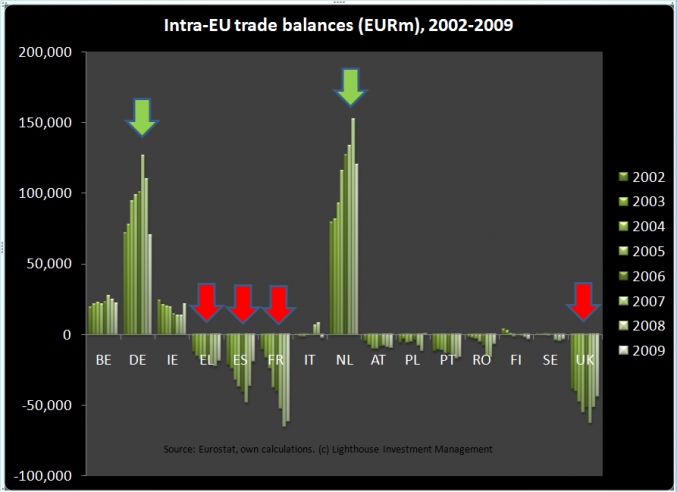

Let’s look at intra-EU trade balances[14]:

Germany and, especially, the Netherlands enjoy large positive trade balances – at the expense of (almost) everybody else. I don’t know what the Dutch are up to – they run a large trade deficit with non-EU countries, but a huge positive trade balance (>20% of GDP) with their EU counterparts. UK, Greece, Spain, Portugal and France, among others, have trade deficits within the EU and with non-EU countries. This is a clear sign they would need a lower exchange rate. With Mr. Bernanke pretending to print money (he isn’t – but the US government is: by running large fiscal deficits) the Euro is unlikely to weaken versus the dollar. Meaning: those countries probably would need to get out of the Euro (not the UK – fortunately for them, having its own currency).

In the past, large trade imbalances would lead to pressure on exchange rates to adjust (as regularly done under the European Exchange Rate Mechanism). If Greece imported too many goods, the additional Drachma paid to foreign exporters would, all else being equal, automatically lead to a declining exchange rate. But that is impossible in the Euro zone.

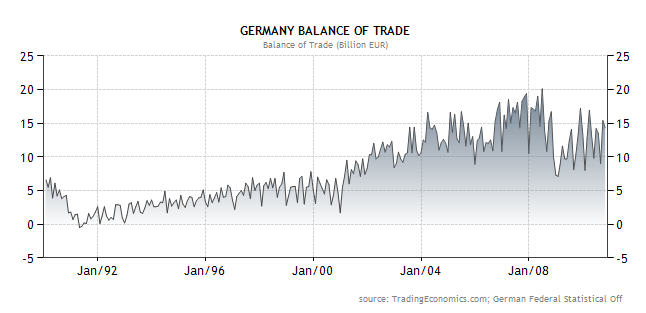

You could probably make a case that Germanys trade balance really started to take off once the Euro inhibited currency adjustments[15]:

Of course, those large positive trade balances allowed German households to save 15-17% of gross disposable income between 2000 and 2008[16]. Greece (apart from Lithuania) was the only country in the EU with a negative household savings rate in 2008[17]. While German households were able to reduce their gross debt-to-income ratio from 105% (2000) to 89% (2008), Greek households saw an increase from 17% to 71% over the same time period.[18] Ironically, excess German savings are what fuels German bank lending to peripheral Euro-zone countries, constituting a form of vendor-financing. The circle will be complete once those countries default on their unsustainably high obligations.

Highly indebted banking sectors can even take down entire countries (see Ireland). Once the banking sector debt reaches several multiples of GDP, the government will see itself run out of money in an attempt to save the banking system. Any government guarantees (for deposits) then become worthless, as witnessed by the recent accelerating drain of Irish bank deposits (EUR 40bn in December, EUR 110bn or 60% of GDP in 2010)[19]

How does the end game look like?

Rob Parenteau looks at the example of Spain[20]. To reduce its fiscal deficit from 10% to 3% within three years (the “Stability and Growth Pact”), the trade balance must improve by 7% of GDP or the private sector must leverage up by the same amount (or a combination of those two). Improving the trade balance by this amount seems unlikely, as Spain’s main trading partners have to undergo same austerity measures, which will curb domestic demand. This leaves only a further leveraging of the private sector. Rob writes: “It is highly unlikely Spanish businesses and households will wish to raise their indebtedness in an environment of 20% plus unemployment rates, combined with the prospect of rising tax rates and reduced government expenditures as fiscal retrenchment is pursued.”[21]

It is not a coincidence that the lowest unemployment rate in the EU can be found in the Netherlands (4.3%)[22], while Germany recorded its lowest number of unemployment workers since 1992[23].

With Spanish youth (under age 25) unemployment rates of 42.8%[24] (not a typo) it is only a question of time until someone, after a long day of staring at the Mediterranean Sea, thinks “I need to start a riot”.

What if the private sector does not want to or cannot increase debt? “Prices and wages in Spain’s tradable goods sector will need to fall precipitously, and labor productivity will have to surge dramatically, in order to create a large enough real depreciation.”[25]

Declining wages and deflation make it difficult to service debt, resulting in bankruptcies. And here is the irony: “As it turns out, pursuing fiscal sustainability […] will in all likelihood just lead many nations to further destabilization of private sector debt.”[26]

Rob concludes: “[…] for the sake of the citizens in the peripheral Euro zone nations now facing fiscal retrenchment, pray there is life on Mars that exclusively consumes olives, red wine, and Guinness beer.”[27]

You cannot cure the situation by lending more money to countries with a chronic trade deficit. It makes the situation worse (interest payments add to the outflows).

There are only two solutions: continue the current path of austerity and deflation until a large bank or en entire country blows (financially) up (at which point the country might as well leave the Euro) or have Germany and the Netherlands exit the Euro for the benefit of the Euro.

Strong countries leaving the Euro will less likely lead to bank runs than weak countries leaving.

Germany and the Netherlands might want to create a “turbo-Euro” which trades within a certain range towards the “Club-Med-Euro” with the possibility of realignment if necessary. The Germans would be well advised to act before discontent with the Euro, the EU and austerity overwhelms peripheral government.

Unfortunately there is little hope policy makers will abandon their current policy of increasing dams while letting the water run. When the dams finally break, many innocent victims will be swept away.

Alexander F. Gloy is CIO of Lighthouse Investment Management

[1] www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/aktuell.html

[2] “Merkel’s plan could transform the European Union”, in: Der Spiegel, January 31, 2011

[3] “European Union talks on Greek debt as IMF flies in”, in: The Guardian, January 30, 2011

[4] “Irish Central Bank Cuts 2011 Growth Forecast on Fiscal Squeeze”, in: Bloomberg, January 31, 2011

[5] “The National Recovery Plan 2011-2014”, page 111

[6] “Bond Buyer of Last Resort”, in: Wall Street Journal, February 1, 2011

[7] I am indebted to Rob Parenteau for helping me understand the equation.

[8] CofFEE (Center of Full Employment and Equity): Working Paper no 08-10, by: James Juniper and William Mitchell

[9] Eurostat: External and intra-EU trade – Statistical Yearbook – Data 1958-2009, 2010 edition, pages 82-83

[10] Ireland might be a special case as a lot of goods and services just transition through the country to make profits appear in this low-tax environment – but the local population never sees any of the benefits.

[11] Eurostat: External and intra-EU trade – Statistical Yearbook – Data 1958-2009, 2010 edition, pages 82-83

[12] Eurostat: News release 170/2010, November 15, 2010

[13] Eurostat, own calculations

[14] Eurostat: External and intra-EU trade – Statistical Yearbook – Data 1958-2009, 2010 edition, pages 82-83

[15] Source: TradingEconomics.com

[16] Eurostat: Economic Statistics, 2010 Edition, page 149

[17] Eurostat: Economic Statistics, 2010 Edition, page 149

[18] Eurostat: Economic Statistics, 2010 Edition, page 151

[19] “Irish bank flight quickens despite EU rescue”, by: Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, in: The Telegraph, February 2, 2011

[20] “Will the Earnest Quest for Fiscal Sustainability Destabilize Private Debt?”, by: Rob Parenteau, in: Outside-the-box by John Mauldin, March 9, 2010

[21] “Will the Earnest Quest for Fiscal Sustainability Destabilize Private Debt?”, by: Rob Parenteau

[22] http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Unemployment_statistics

[23] “German Joblessness Falls to 18-Year Low”, Bloomberg News, February 1, 2011

[24] http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Unemployment_statistics

[25] “Will the Earnest Quest for Fiscal Sustainability Destabilize Private Debt?”, by: Rob Parenteau

[26] “Will the Earnest Quest for Fiscal Sustainability Destabilize Private Debt?”, by: Rob Parenteau

[27] “Will the Earnest Quest for Fiscal Sustainability Destabilize Private Debt?”, by: Rob Parenteau

One response to “What a taifun in Vietnam taught me about the Euro crisis”

[…] By Alexander Gloy, CIO of Lighthouse Investment Management […]